I’ve been investing since 2007, and I’ve always been steadfast in the belief that capital growth is the key ingredient you need to get right if you are to build a property portfolio that will allow you to produce meaningful wealth. I know this to be true from both a theoretical, financial modelling point of view, but also from first hand experience.

I’ve built a significant property portfolio over a long-time, and the way I’ve done this is not via continually saving for deposits, nor was it via collecting a lot of cheap properties that produce $20 a week in net income, but rather it was built off the back of strong capital growth and some sensible financial planning. In fact, I haven’t ever had to dip into my savings to fund a property purchase (or a renovation for that matter) since the first one I purchased. Each subsequent property was purchased using equity made available through capital growth.

Conversely, however, I’ve seen far too many examples of investors who have chased cash-flow exclusively, and who have seen their portfolio growth prematurely halted as they haven’t been able to raise funds for a deposit for another property. So let’s dig a little deeper and unpack a few things, to help explain why capital growth is so important when you’re looking to build a property portfolio.

The importance of capital growth when building a portfolio

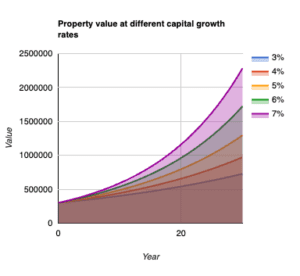

Let’s take a simple mathematical example, to show what happens to the value of a single property, when assuming different capital growth rates.

This is obviously a simple representation, and shows five different theoretical $300,000 properties that grow at different capital growth rates, ranging from 3% per year to 7% per year. After 10 years, the property that grows at 7% will have produced around $187,000 more equity than the property that grows at 3%, and after 20 years this increases to around $619,000. These are big differences, and can make a huge difference to an investor’s retirement planning. It’s easy to graph things out and just pluck out random numbers to make a point on a model. However, the reason I’ve chosen 7% is that is the yearly average growth rate I’ve achieved for the properties that I’ve owned for more than 10 years (it’s actually a little higher). I’ve also seen many investors make far less, including countless who have invested over the long term and not made a cent.

This is obviously a simple representation, and shows five different theoretical $300,000 properties that grow at different capital growth rates, ranging from 3% per year to 7% per year. After 10 years, the property that grows at 7% will have produced around $187,000 more equity than the property that grows at 3%, and after 20 years this increases to around $619,000. These are big differences, and can make a huge difference to an investor’s retirement planning. It’s easy to graph things out and just pluck out random numbers to make a point on a model. However, the reason I’ve chosen 7% is that is the yearly average growth rate I’ve achieved for the properties that I’ve owned for more than 10 years (it’s actually a little higher). I’ve also seen many investors make far less, including countless who have invested over the long term and not made a cent.

The above looks at the example of a single property, and shows the importance of getting asset selection right. However, this is magnified when we look at what happens when we want to start building a portfolio. Correct asset selection in the beginning will allow you to purchase a second property sooner, and, all going well, build your asset base that bit more quickly.

Let’s explore what it looks like to add a second property. In general terms, and subject to their borrowing guidelines and an investor’s servicing, banks are usually happy to lend up to 80% of a property’s value without imposing additional fees such as LMI. They’ll often lend more, but for this example we’ll just keep it simple. So, if you’ve experienced significant equity growth, like in the 7% example above, there’s an opportunity to access this equity to release a deposit for a second property. Let’s assume the second property was also $300,000, and was financed with a standard 80% investment loan. This would require the investor to have a 20% deposit ($60,000). A common rule of thumb is to allow 5% for purchasing costs such as stamp duty and legals, so we would allow for an additional $15,000 in this example, for a total of $75,000.

Can the investor use the growth in their first property to generate a deposit and purchasing costs of $75,000 to purchase a second property? Let’s assume the same $300,000 property example above was initially financed at an 80% debt level ($240,000 loan) and assume it has produced an average 7% year on year growth. After 4 years, the property would be valued at just over $393,000, which is growth of just over $93,000. However, the bank won’t just give the investor a cheque for $93,000. Rather, using an 80% mortgage example again, they’ll let them borrow up to 80% of the value of the property less any existing debt. In this case it would allow the investor to access almost $75,000 ($393,000 x 80% less existing debt of $240,000), normally via a top-up loan or a line of credit.

Given the investor has released $75,000 in equity, they could theoretically purchase that property. However, it wouldn’t allow for any cash-flow buffer or unforeseen costs, so it would be better for that investor to perhaps wait for more growth, or purchase a slightly cheaper property. The method described above is a common way that property investors grow their portfolios, and is the exact way that I’ve grown mine over the years. There’s a lot more to consider, such as buffers, property strategy, renovations, income targets, sell down strategies etc, but this gives you a simple overview of the mechanics of using equity in one property to create the deposit to purchase a second property.

However, what happens if the property only grows at 3% per year? Well, then things look quite different. Using the same example, instead of being able to purchase another property after around 4 years, the investor would need to wait for more like 10 years to create sufficient equity. There’s one more thing to consider, however. Growth is obviously not linear. It’s all very nice to create a data set and show theoretical examples of how to make money using property. But, in the real world things don’t just increase in a linear, orderly, manner. There are ups and downs and sideways periods. And, on occasion, there are sudden bursts of growth, like we saw in Sydney and Melbourne in the few years after 2013. What this means, is that there may be opportunities for investors to invest in a second property sooner than first thought, if there has been earlier (or stronger) than forecast growth. This was certainly my experience, and this allowed me to purchase a 2nd and then 3rd property, and so on. The other thing, best left for another article, is how you can use value add strategies such as renovating to fast track your equity growth. This is certainly a strategy I use with clients when it suits their individual circumstances.

Capital growth as a cash-flow management tool

Surely, I am not going to argue that buying capital growth focused properties, which might not have the strongest yields, is actually beneficial from a cash-flow management point of view!? Yes, yes I am. But…with a caveat. This is about cash-flow management in an overall sense, and not just about cash-flow on an individual property. You see, if you can find a property that has good long-term capital growth prospects, you can position yourself to benefit from structuring your portfolio to become more robust into the future, from a financial management point of view. Banks like to lend money on property, it’s an important part of their business. But they don’t like lending money on just any old property. They’re quite specific about what they do like, and what they don’t like.

Let’s revisit the previous example, with the $300,000 property growing at a solid 7% per year. As we noted, after 4 years the property will have grown significantly and the property investor might want to consider investing in another property. However, what if they weren’t keen on that, or just wanted to take a breather? Well, there’s a second option they could do with their new found equity, and it has important cash-flow management implications. I noted earlier that a standard way to access equity is via either a top-up loan against the first property, or via a line of credit. Rather than releasing funds to immediately use for a second purchase, the investor could look to release these funds and just keep them there as a rainy day fund (for investment purposes) or to act as a cash-flow buffer. It’s important to run everything by your accountant to make sure you’re staying on the right side on the ATO, before making these decisions, but this can be a sensible way to use capital growth as a cash-flow management tool. To be clear, I’m not advocating borrowing for borrowings sake, and it is important that you are very clear in understanding the risks involved in taking on more debt. This is a strategy I’ve employed numerous times over the years, and if used correctly, it can be an important tool in your investing toolkit. Again, please seek advice from licensed professionals.

A note on negative gearing

Negative gearing has been in the press…a lot…recently. It is true that, when looking for capital growth focused properties, one of the trade-offs has traditionally been a lower yield than you might get from other properties. However, it’s important to realise that negative gearing is an outcome, it’s not a strategy in and of itself. Also, and very importantly, it’s only at a point in time. I have purchased numerous properties which started off as negative geared properties, and then over time (chiefly due to rental growth and not debt pay down) they have flipped to become cash-flow positive.

The above chart, which admittedly is very simplified, shows a scenario of a $300,000 property that has an initial yield of 5% ($288 per week at purchase), with average rental growth of 3% per year, versus a higher yielding 6% ($346 per week at purchase) property, which sees its rent per week grow at 1% per year. In this example, you’ll see that there is an inflection point at around year 10 where rents on the lower yielding property are actually higher in a dollar per week sense, than the higher yielding property.

You might ask why I’ve chosen the two yield examples of 5% and 6%. Currently, I’m finding properties for clients at and around the 5% yield mark, in highly desirable blue chip suburbs of major capital cities, with low vacancy rates and the requisite capital growth drivers that I look for. The second example, 6%, is an often bandied about ‘minimum’ required yield said to be needed to create a cash-flow positive portfolio. The issue is, as I’ve highlighted above, if you first search for yield and then look for growth, in my experience you will come up short. My approach is to first look for the capital growth drivers, and then seek to overlay this with a required yield number. I believe it is a far better approach.

This all sounds wonderful, but does it work in practice? Again, using my own personal experiences, I own properties that have benefited from significant long-term rental growth. Whilst it was not close, in percentage terms, to the capital growth, it has nonetheless been the catalyst to see these properties become cash-flow machines in their own right. However, I have also seen first hand what can happen when investors get it wrong, and end up with properties that aren’t growing from either a capital growth point of view or seeing any substantial rental growth. It’s a very tricky position to find yourself in, and it can set you back substantially when you’re trying to build a property portfolio. Of all the costs associated with property, opportunity cost is the one that is most often overlooked.

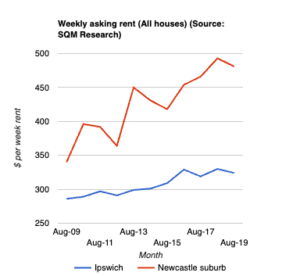

So, how do these numbers play out when looking for real world examples. I decided to do some analysis on two cities I’m very familiar with, one as I own a couple of properties there (a suburb in Newcastle), and one because it is currently very popular amongst the cash-flow positive crowd (Ipswich). They provide an interesting comparison, as both are large non-capital cities that have being impacted by changes to the industrial landscape in recent times.

I’ve used data from SQM Research, and used the weekly asking sale price as a proxy for capital growth and weekly asking rents as a proxy for rental growth. These won’t be perfect measures, as in both cases the actual sold value and the rented level could differ from the asking amounts, but they serve as useful data points for this analysis to illustrate a point. In both cases I’ve used the headline number for “all houses”. Note: As we’re looking at weekly data, presented on a monthly basis, in each case I’ve taken the first week’s data to represent the month.

The graph below shows the trend of asking rents over the last 10 years. The red line, representing the suburb in Newcastle, shows a gradual increase and reflects an average growth of 3.5% per year, slightly higher than the 3% example used above. The blue line, showing Ipswich, shows little growth, and in fact only averaged 1.3% annual growth in asking rental prices over the same period.

Having a look at weekly asking sales price growth, we can see a similar, though more marked result. In this example, the asking weekly sales price for Ipswich hasn’t increased at all over the 10 year period. In other words, it hasn’t kept pace with inflation. Again, this doesn’t correspond perfectly to capital growth, as it doesn’t take into account vendor discounting or sales that didn’t proceed, but it certainly provides an indication as to the direction of the market over that time period. In comparison, the Newcastle suburb has seen average weekly asking prices increase 5.6% over the same period. This is also consistent with the capital growth I’ve experienced in the suburb across the properties I own there.

This is not to say that if you invest in Ipswich now you won’t make money, and that if you invest in Newcastle you’re guaranteed to make a killing. Far from it. As with all locations, there are property cycles at play that make some times better than others in which to invest. This analysis isn’t meant to guide your decision on whether to invest in either of these locations now, but rather to help provide a cautionary tale of what can go wrong. In the case of investors who purchased 10 years ago in Ipswich, they haven’t lost any money in actual dollar terms, from a capital point of view. But they have missed out on other opportunities, where their money could have worked for them better, and it’s likely they have lost money when you take into account holding costs.

The importance of a portfolio approach to investing

The above analysis gives you some background on the benefits of favouring a capital growth strategy as a basis for building a property portfolio. It is, however, not the only strategy available. It’s hugely important that each property is chosen based on how it will impact your portfolio over all, and this means that on occasion it may be sensible to look for higher yielding properties such as commercial properties or even short-term letting options such as AirBNB. As always, if you invest with the end in mind, and only buy properties that advance you toward this goal, you’ll be in a much better position than most property investors.

Please note: the above information and analysis does not constitute financial advice in any way, and it should not be relied upon. It’s important that you seek guidance from licensed professionals, who can provide advice based on your individual needs. No investment decision or activity should be undertaken on the basis of this information without first seeking qualified and professional advice.